Civil War Data 150 (“CWD150”), is a collaborative project to share and connect Civil War related data across local, state and federal institutions during the four year sesquicentennial of the American Civil War, beginning in April of 2011. The project will utilize Linked Open Data to find and create connections between archives and help increase the discovery of these resources by researchers and the general public alike.

Civil War Data 150 (“CWD150”), is a collaborative project to share and connect Civil War related data across local, state and federal institutions during the four year sesquicentennial of the American Civil War, beginning in April of 2011. The project will utilize Linked Open Data to find and create connections between archives and help increase the discovery of these resources by researchers and the general public alike.

Technical Opportunities

CWD150 is exploring the use of Linked Open Data within libraries, archives and museums, and extending the usability and availability of structured data. According to a concise definition on LinkedData.org, “the Web enables us to link related documents. Similarly it enables us to link related data. The term Linked Data refers to a set of best practices for publishing and connecting structured data on the Web.” Open data refers to metadata or data either in the public domain or licensed with Creative Commons Attribution.

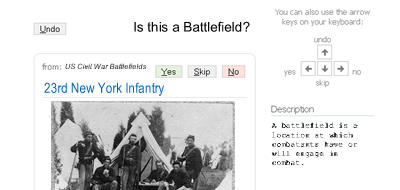

Linked Open Data allows us to identify named entities (in this case, regiments, officers, battles, battlefields, flags, etc), and use standardized World Wide Web formats to link data to these entities. For instance, the Library of Congress has a photo of soldiers from the 23rd New York Infantry. By using this format to link that photo to the National Park Service’s description of the 23rd New York, others are able to not only follow that link to learn more about that regiment (like when and where it was formed), but they can also follow other links to any other photos or books or journals that have used the same format to describe itself as pertaining to the 23rd New York. Because these web formats for linking data are not unique to libraries or archives, they give us the opportunity to link data not only between institutions, but to other data and websites on the World Wide Web.

Educational and Crowdsourcing Opportunities

One of the first steps of this project, and any Linked Data project, is to build a common language for the entities we’re talking about. In this case, we may use a source that most Civil War scholars and historians agree is authoritative, like the descriptions and histories of regiments maintained online by the National Park Service. With that as a basis, we can then take data from various sources, like the descriptions describing the Library of Congress photos, and create links. Some links may be able to be parsed out using algorithms and scripts, but many more will require human judgment.

If we’re going through a (virtual) stack of photos, it’s relatively easy for a person to identify whether or not this is a portrait, a battlefield, or a group photo, but this information is extremely useful to help us begin categorizing and linking photos to things. For these sorts of tasks, we’re creating data games that help users make these sorts of identifications, and can also be integrated into middle or high school curriculum. Students will interact with photographs, journals, maps, and personal information of actual Civil War soldiers, while contributing important information to the project.

Using Freebase RABJ queues to receive multiple human judgments.

More complicated questions may require a little more research, for which we’ll ask help not only from students, but from American Civil War enthusiasts who have more familiarity with the topic. Suppose we’ve sorted a collection of photos into three groups: portraits, battlefields, and group photos. We might next create a stack of the photos described as battlefields, and ask users to place them on a map.

As you can see, the more information that is contributed, and the more links that are made, the more useful this information becomes!

Putting Together the Pieces: Enabling Web Applications

So what do we do with this web of data we’ve created? How is this any better than just doing a Google search to discover photos about the 23rd New York Infantry?

One major difference is that these collections of links, using a standard format, give us the ability to discover and present data in any number of web applications that can be created and modified by selecting one or another element. For instance, we may have started with a collection of photos of the 23rd New York, but once we’ve linked various sets of data together, now we can see their troop movements on a timeline or a map. We can follow them through their various battles; we can read what the soldiers wrote home about; we can learn how many died in battle, and how many returned home after the war. At any point, it’s possible to follow the links back to the source data at the participating institutions.

Using Simile and other web tools, Linked Open Data can be relatively easily rendered into attractive graphic presentations. Imagine maps of battles, timelines of troop movements, or graphs of troop casualties over time, all based on open data.

Another key difference is that Linked Data can give us the ability to deduce information based on a single input. For instance, a survival probability application may let a user choose a town, and the application would show which regiment they would’ve joined, which battles they would have served in, and what the probability of survival would have been based on regimental casualties.

Creating links across various sources will enable unique presentation and discovery never before possible with Civil War data.